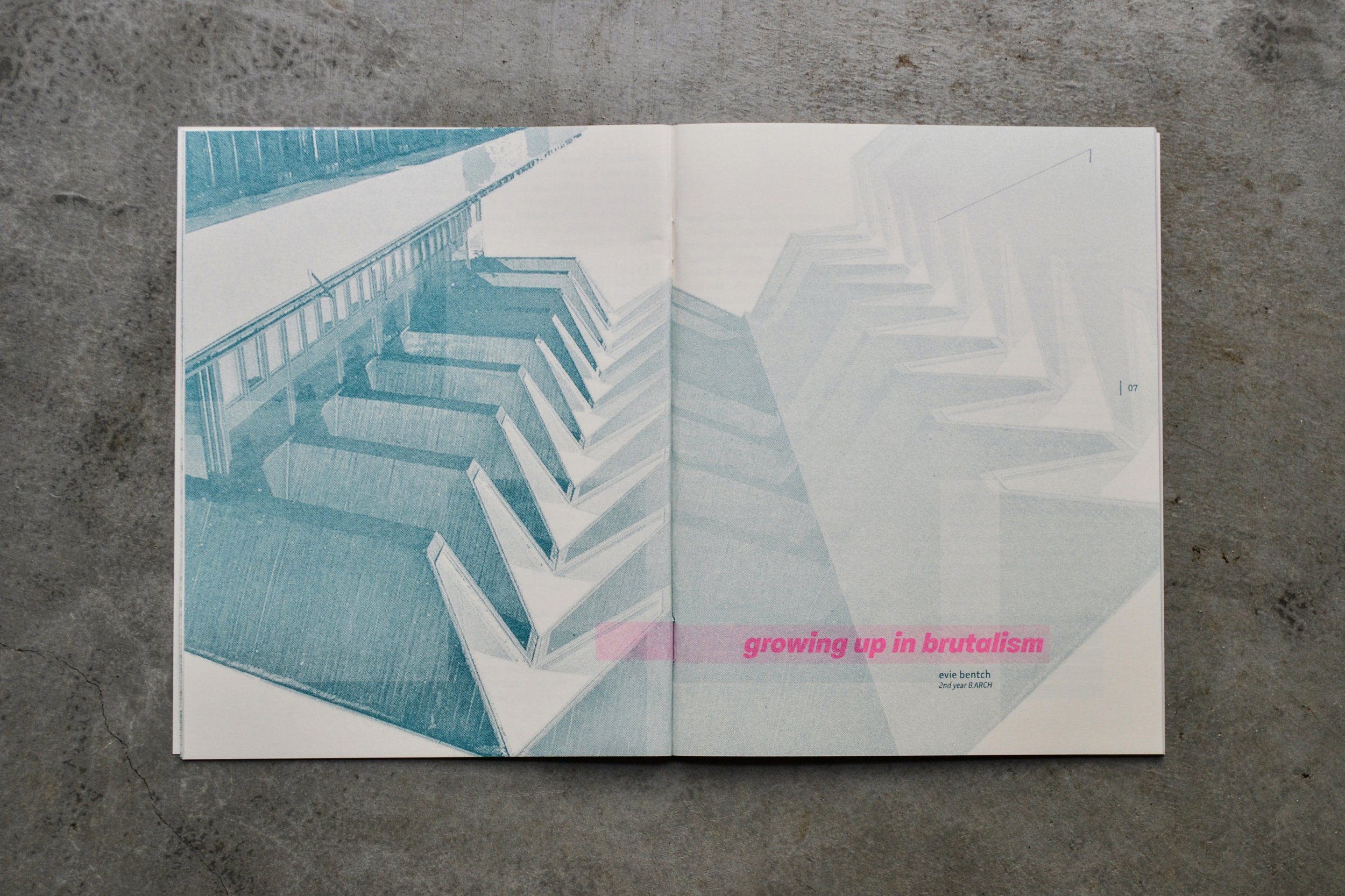

GROWING UP IN BRUTALISM

by Evie Bentch

Whether or not you are particularly

opinionated about architecture, you have likely walked by a brutalist

structure in your lifetime and stared up at the concrete, characterless form in disgust.

There are entire Facebook groups devoted to ranting about buildings that may be too outmoded to be modern, but too young to be classic. This strong reaction did not escape me as a six-year old on my walks to school past the panelház, rows of sand-colored

apartment buildings on the outskirts

of Budapest. Even then, with no knowledge of Le Corbusier, communism, and post-war modernism, I somehow felt offended by these structures.

The rigid built environment that

housed my childhood imposed tangible

remnants of the communist regime that had fallen in Hungary just a decade before I was born. At school, the flat white paint covering the hallways, classrooms, and gymnasium matched a strictsystem of instruction and punishment.

The lack of variation between the structures reflected an emphasis on uniformity that was embedded into every aspect of learning.

My early sentiment about what I later

learned to call Brutalism was not far off from the intentions of the soviet-rooted design agendas that swept through Budapest and other cities in Eastern Europe in the 1960s and 70s. Marxist-Leninist ideals of collective consciousness were translated into 100-story stacks of affordable living compartments. The hatred of ornamentation was cast into the flat concrete facades of municipal skyscrapers.

In non-communist urban landscapes, Brutalism fit into the postwar context of transparency and moral seriousness. To the most passionate opponents of the style, the erection of the concrete jungle portrayed an ignorant rejection of the classicist architectural languages that had taken hundreds of years to develop.

For a style that is so closely associated

with political and economic ideals

that have lost relevance in society,

Brutalism is not being forgotten,

and is in the wake of rebranding. The

antiquated emphasis of ethic over

aesthetic is being reintroduced into

the modern architectural dialogue, and

a small part of the public is beginning

to embrace the trend.

For some self-named brutalists this response may be

one of nostalgia, heightened by the demolition binge that has taken place

across cities over the past few years.

While I doubt the concrete

environment that I grew up in will ever lose its hostile associations in my memory, I admire the revolution that it represents. In this current age of waning political trust, the exposed truthfulness of Brutalist forms may come to signify a new moral importance in society that supersedes design impressions.